As DC-SIGN, langerin is a type II C-type lectin, almost exclusively expressed on epidermal LCs, but also present on dermal CD103+ DCs and lymph node resident CD8+ DCs (Valladeau, J, Ravel, O, Dezutter-Dambuyant, C, et al., 2000, Romani, N, Clausen, B. E, & Stoitzner, P. 2010, doyaga, J, Suda, N, Suda, K, et al., 2009). LCs is a subset of DCs, whose role is not completely clear. Although initially they were assumed to function as APCs, like dermal or stromal DCs (Hunger, R. E, Sieling, P. A, Ochoa, M. T, et al., 2004), the accumulating evidence of their fail to present antigens from various viruses and parasites to T cells activation and the observation that LCs induce T regulatory cells supports the presumption that these cells may have an immunosuppressive, tolerogenic role (Stoitzner, P & Romani, N. 2011).

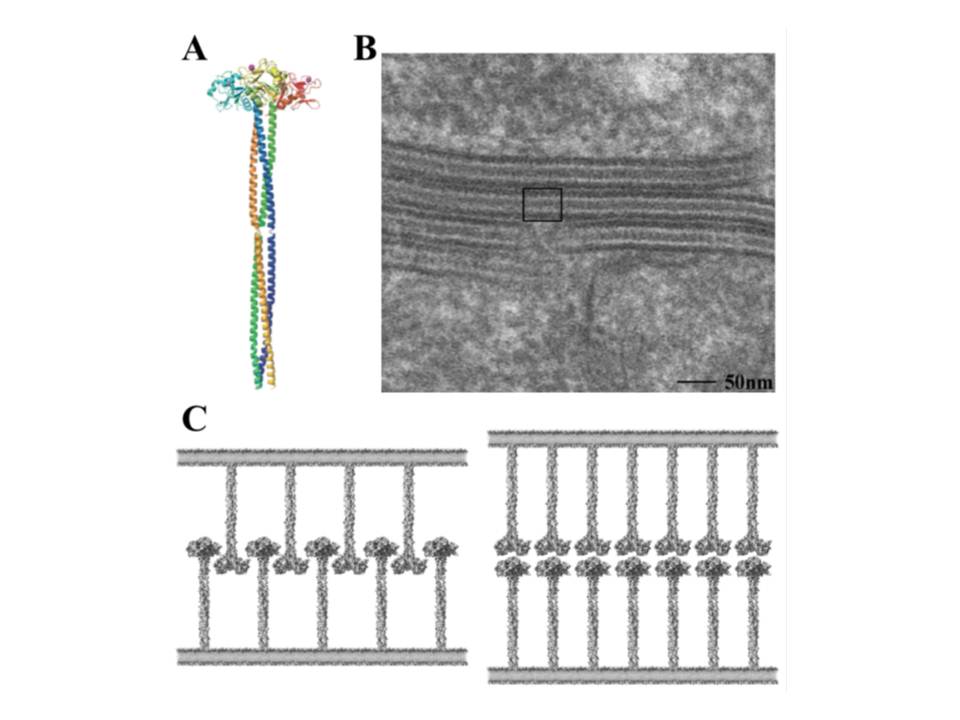

A characteristic hallmark of LCs is the Birbeck granules (fig.16), and langerin has been shown to be the main component and responsible for the formation of these tennis racquet or

rod-shaped membranous structures (Valladeau, J, Ravel, O, Dezutter-Dambuyant, C et al., 2000, Cunningham, A. L, Carbone, F, & Geijtenbeek, T. B. H. 2008, de Jong, M. A. W. P, Vriend, L. E. M, Theelen, B, et al., 2010). It binds pathogens through the recognition of high-mannose structures Stambach, N. S & Taylor, M. E. (2003) present on viral envelopes, mannan and β−glucan structures on fungi (de Jong, M. A. W. P, Vriend, L. E. M, Theelen, B, et al., 2010).

As already described in sub-subsection 2.2.1.2, langerin is particularly important in protection against HIV infection since it captures HIV-1 virions by binding to envelope glycoprotein gp120, and this leads to their degradation in BGs (de Witte, L, Nabatov, A, Pion, M, et al., 2007). The anti-fungal function of LCs is suggested as well, with a central protective role exerted also by langerin (de Jong, M. A. W. P, Vriend, L. E. M, Theelen, B, et al., 2010).

4.1. The structure and carbohydrate recognition by langerin

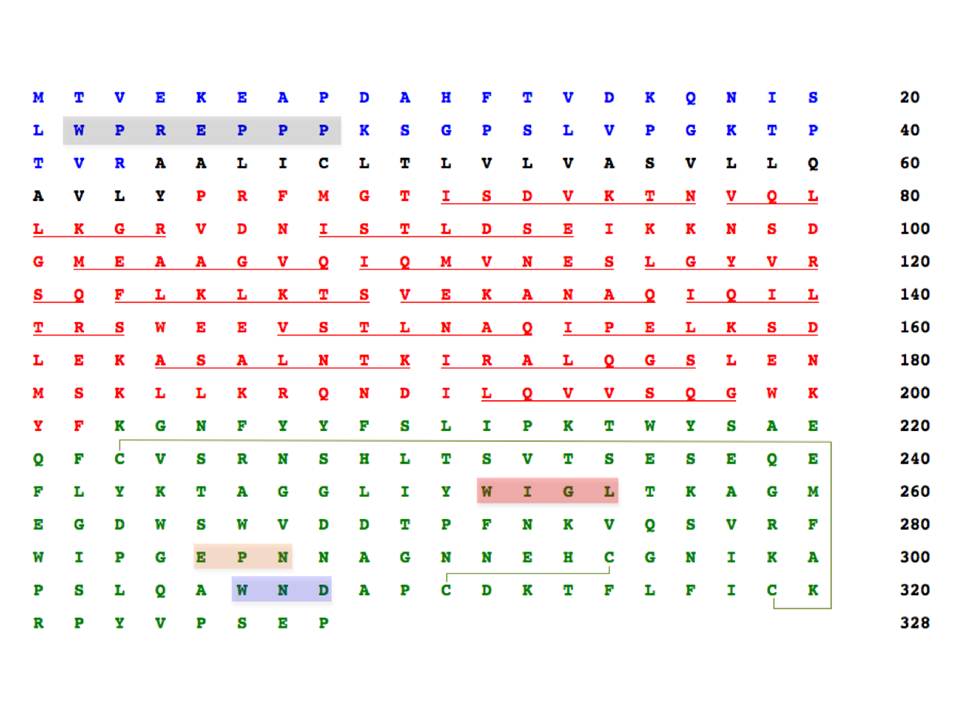

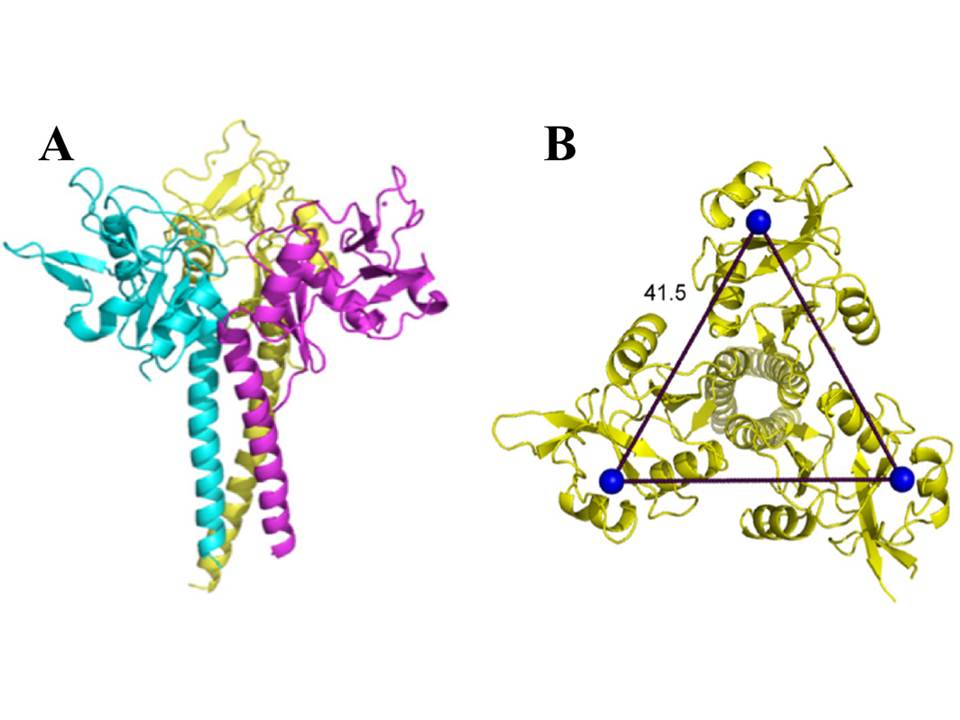

Langerin is a type II transmembrane receptor (328 amino acids, 37.5 kDa) with an overall molecular organization similar to DC-SIGN and other CLRs : it consists of N-terminal cytoplasmic domain, transmembrane domain, neck region, and a C-terminal C-type CRD (fig. 17) (Valladeau, J, Ravel, O, Dezutter-Dambuyant, C, et al., 2000). The cytoplasmic domain of langerin contains a proline-rich signaling motif (WPREPPP), which could function as a docking site for signal transduction proteins, and indeed, it was demonstrated to be important for langerin intracellular targeting (Thépaut, M, Valladeau, J, Nurisso, A, et al., 2009). Nonetheless, the role of langerin signaling is still obscure (van den Berg, L. M, Gringhuis, S. I, & Geijtenbeek, T. B. H. 2012).

The sequences of cytosolic, transmembrane, neck region, and CRD domains are in blue, black, red and green letters. The potential proline-rich signaling motif is highlighted in grey, and the conserved motifs defining sugar specificity and Ca2+-coordination are in orange and blue. The conserved WIGL motif is in red. The putative heptads contributing to coiled-coil formation are individually underlined, and the disulphide bridges are depicted by light green lines

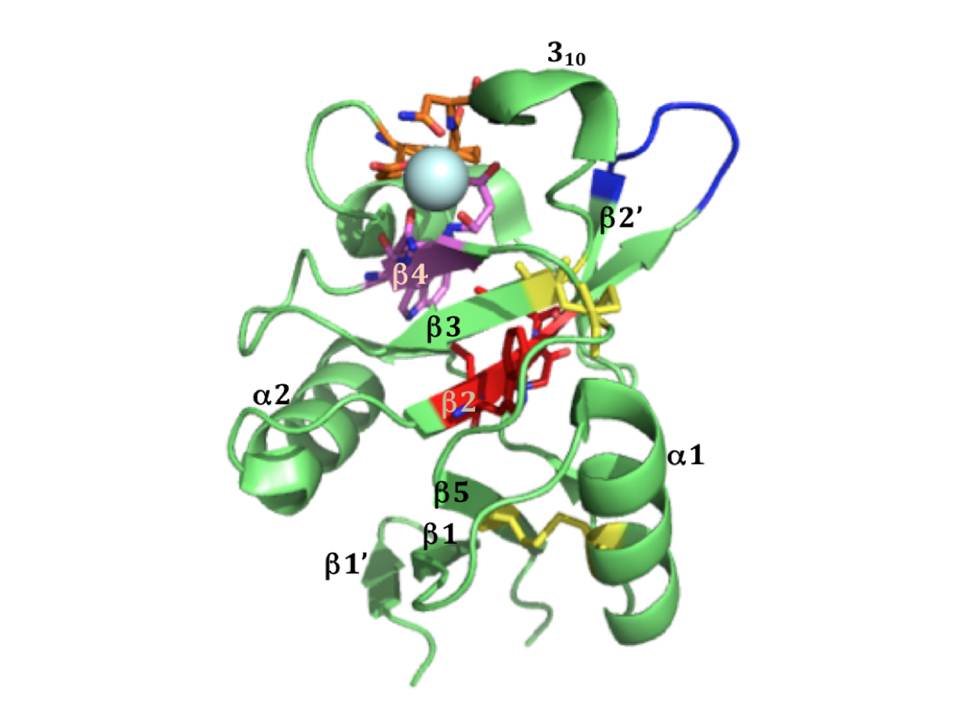

The CRD of langerin (fig 18) contains EPN motif indicating its specificity for mannose type sugars. A glycan array analysis using truncated trimeric langerin, has revealed several types of carbohydrates as ligands of langerin (Feinberg, H, Powlesland, A. S, Taylor, M. E, & Weis, W. I. 2010). As expected, langerin bound high-mannose N-linked oligosaccharides, however, the only fucose-based ligand of langerin was blood group B antigen (Gal α1–3 (Fuc α1–2) Gal). Moreover, a peculiar property of langerin to bind glycans terminating in 6-sulfated galactose was also found (Feinberg, H, Powlesland, A. S, Taylor, M. E, & Weis, W. I. 2010) that explained the ability of langerin to recognize keratin sulphate (Tateno, H, Ohnishi, K, Yabe, R, et al., 2010).

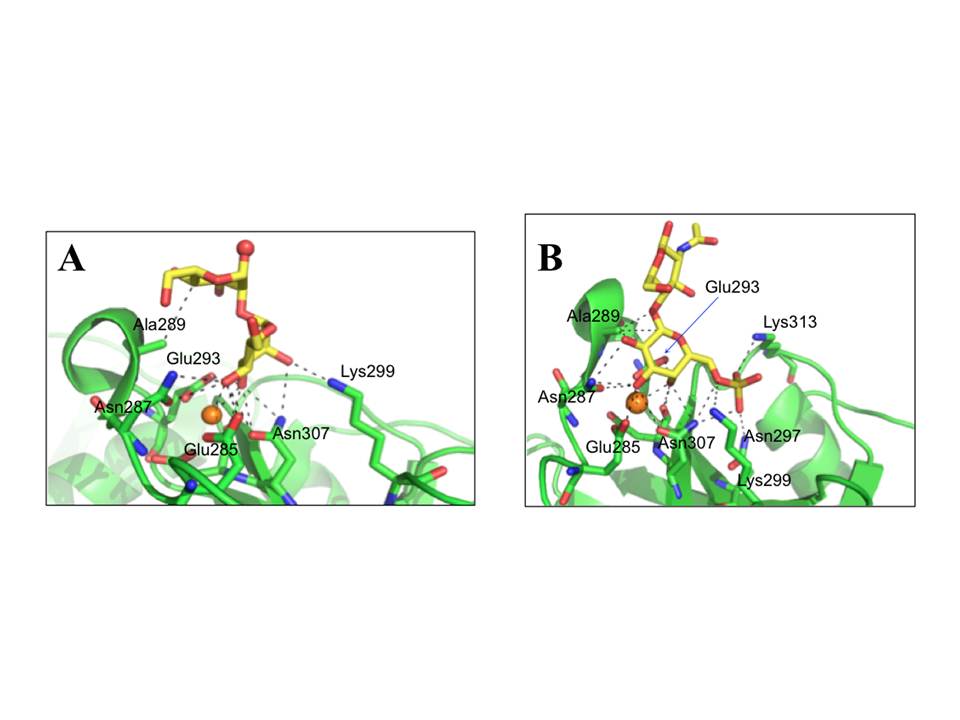

Structural studies of ligand recognition by langerin revealed that it binds high-mannose structures through non-reducing terminal mannoses and internal Man α1-2 Man (fig. 19A), which has multiple binding modes in the conventional Ca2+-dependent sugar-binding site. The binding mode of this non-reducing mannose residue is virtually the same as mannose monosaccharide (pdb:3P7G), except that it is 180° flipped by the axis perpendicular to C3-C4 bond. In contrast to DC-SIGN, langerin has only a small extended binding site that contacts other sugar residues in high-mannose oligosaccharides, and better binding affinity to these oligosaccharides compared to mannose may be a statistical effect of having multiple available mannose residues, as is in case of DC-SIGN (Feinberg, H, Taylor, M. E, Razi, N, et al., 2011).

A, Mana1-2Man in a likely preferred and favored binding mode in the context of longer oligosaccharide with nonreducing mannose coordinating to Ca2+ and oxygen atom that would be linked to the oligosaccharide shown in red sphere (pdb: 3P5F). B, 6SO4–Galb1–4GlcNAc (pdb:3P5I). The Ca2+ ions are shown as orange spheres.

It was also demonstrated that langerin is unique among C-type CRDs since apart of binding mannose/fucose type sugars, it is also able to interact with galactose-based saccharides : it recognizes 6SO4–Gal residues that are present in keratan sulfate as 6SO4–Galb1–4GlcNAc repeating unit (Tateno, H, Ohnishi, K, Yabe, R, et al., 2010). In crystal structure of langerin CRD in complex with 6SO4–Galb1–4GlcNAc (fig. 19B) the galactose residue was found to make coordination to Ca2+ by axial 4-OH and equatorial 3-OH groups, and the galactose residue packs against Ala289. Finally, the SO4 group makes salt bridges with Lys299 and Lys313 (Feinberg, H, Taylor, M. E, Razi, N, et al., 2011).

Trimeric structure of langerin and its role in BG formation

The neck region of langerin is composed of the series of heptads (fig. 17), although these repeats are not as obvious as the tandem 23 amino acid repeats in the neck of DC-SIGN. These heptads are responsible for the oligomerization of langerin into trimers (fig. 20A) (Stambach, N. S & Taylor, M. E. 2003, Feinberg, H, Powlesland, A. S, Taylor, M. E, & Weis, W. I. 2010).

The trimeric langerin is rather a rigid unit with the CRDs in fixed positions as can be seen in the crystal structure of the truncated trimeric langerin : the CRDs make multiple contacts with the neck region and this leads to the arrangement of primary sugar-binding sites at fixed positions separated by a distance of 42Å (fig. 20B). The only significant flexibility in the CRD was observed at the loop region comprising residues 258-262 (fig. 18), and results most likely due to the absence of auxiliary Ca2+ sites that are present in many other CRDs. This kind of fixed organization of sugar-binding sites may restrict ligand recognition by langerin (Feinberg, H, Powlesland, A. S, Taylor, M. E, & Weis, W. I. 2010).